It is not considered polite to tell someone that they are dying. They may be visibly wasting away, broken, bleeding, redolent of your premonition and condemned to death by disease, by fate, by the hand of the state, but still— it is rude to tell them they will die.

This is because to tell someone they are dying is to banish them, once and forever, from existence. We don’t know where the dead go, anymore than we know where we came from. Being cannot converse with non-being, anymore than a rock can talk to a baby. The miracle of life turns out to be pretty limited, in the final analysis, and we cannot hope to expand on it in our final hour. Rather, we must accept that the narrowing funnel of life ends in a single geometric point of absolute density and no volume; invisible and omnipresent, eternal and nonexistent, and we must accept that when we get there, whatever we know and everything we did will no longer matter, literally.

My father is dying. This much is clear. He is 98 years old and his body is no more than thin skin holding back the sloppy mess of animated tissue that will erupt in chaos when the work of maintaining it is finished. He can barely walk, and spends most days in a chair. He stares out from his chair and sees a world that, despite its age, radiates innocence—even as he himself is steeped in the corruption of having lived almost a whole century. It must be awkward to feel yourself so old in a world still youthful. It must be lonely to have outlived all of your friends.

“Don’t look for a happy ending from all of this,” he tells me. “That’s not what this is about.” This is not a bitter refrain. It is a mere statement of fact. We, Cartesian follies, thinking ourselves into being, are bound to live life such that to die seems sad. Death requires no thinking, and so takes our being, and all that is left is nothing. Of course, there are glorious deaths—in battle, for love, in sacrifice—but these deaths cannot be premeditated, or long considered. The shame in living a full life is the shame of having to die a natural death, which, by our thin existential calculus, resounds ultimately as having lost a fight. To die of natural causes is to be beaten by life.

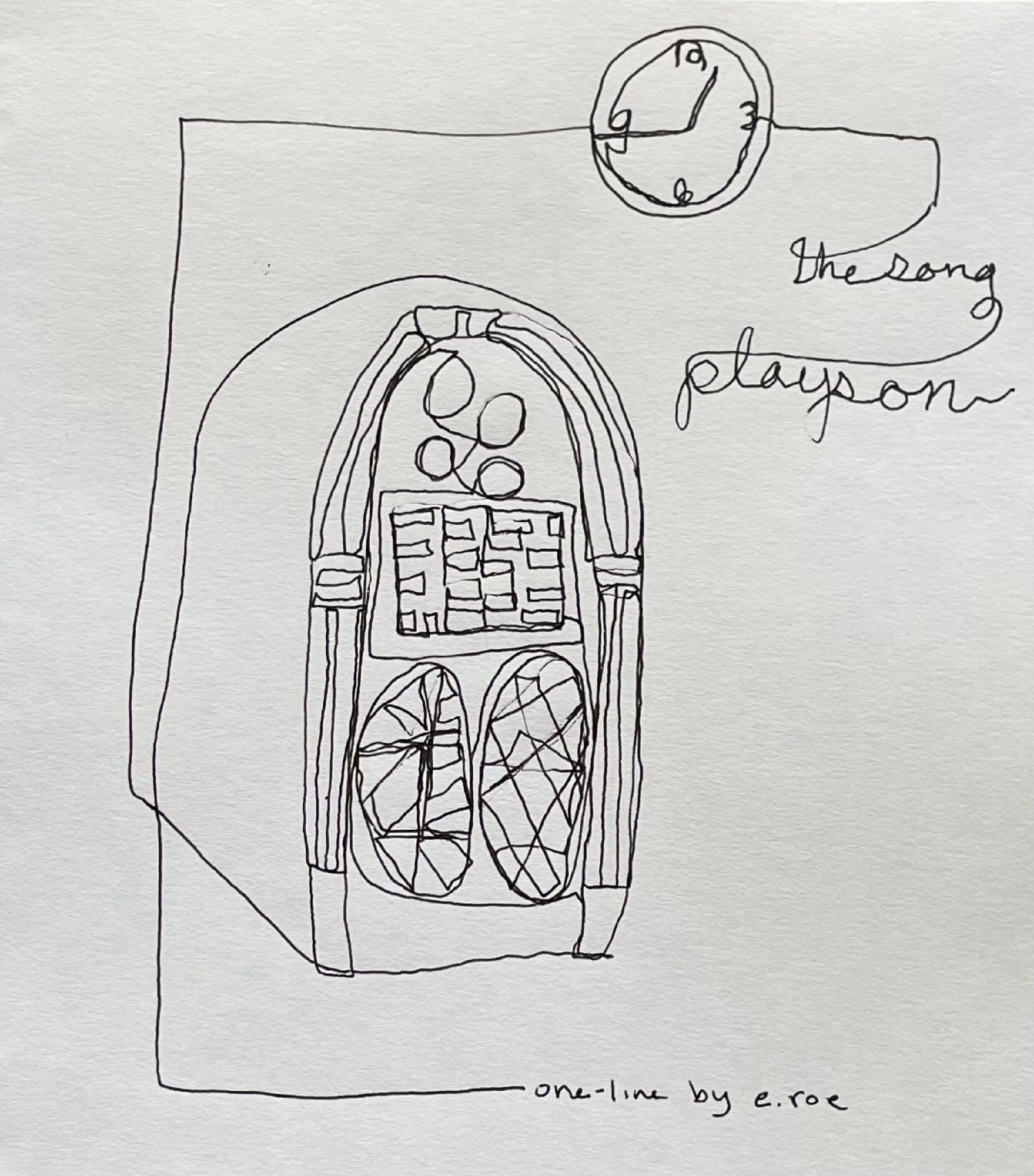

My father can see the mute form of eternity in front of him. It manifests as endless drivel on the television; as the mundane beauty of trees through the window; as the pictures on the walls that surround him; as his wife of many years still floating before his face. But these indexes of the living are mere cloaks for the dark matter of eternity. Behind all this activity is the knowledge that none of it exists in eternity, a place that frightens him because it contains the total of everything he can never know.

I look at this man’s face as he contemplates this quotidian eternity slowly overwhelming his days. His eyes are still clear, though he has stopped wearing glasses. He stopped shaving years ago, and rough strands and patches now cover the deep lines of his face. His hands are bent and bony, with parchment skin covered with bloody patches, subcutaneous bruises, brown spots, and blue veins. The architecture of his skeleton, suspending loose skin over collapsing bone, is clear.

My father walks with a walker, such that his life has been reduced to a zone between 3.2 feet and 5.8 feet from the ground, spread across a walled, rectilinear area extending 12 yards eastward from his bedroom deep within the house he still lives in. The corner he is painted into is as clear and specific as a piece of cutlery. He is almost to the end of that funnel.

When babies are first born, they are suspended in a twilight that owes as much to the mystery of the place they came from as to this one we have drawn them into. A newborn, every time it falls asleep, clearly returns to where it was. Upon awakening, it must discover the strange joy of being alive all over again. They shake this confusion off after a few months, and commit fully to being here, now, but still—those first weeks are revelatory, and show us clearly how little in control we are.

Extreme old age enacts this process in reverse. The claim on life that endured, protected, and animated us through all our years begins to weaken, and the lure of the unknown begins to grow. This grand mystery, which we spend our lives variously ignoring, denying, decrying, or obsessing over, now begins to call back its loan. Soon it will take him. I will search for him, but he will not be here. He will be nowhere.

My father wants to go to this mystery—in theory. He wants to drink his hemlock, say his goodbyes, and return to where he came from—in theory. But even one as philosophically dexterous as he—who has read his Spinoza and rejected his Sunday School homilies—cannot help but bow in fright to the severity of the obscurity into which he now contemplates. To move from existence to non-existence is the biggest paradigm shift he will ever know, and he will not survive it.

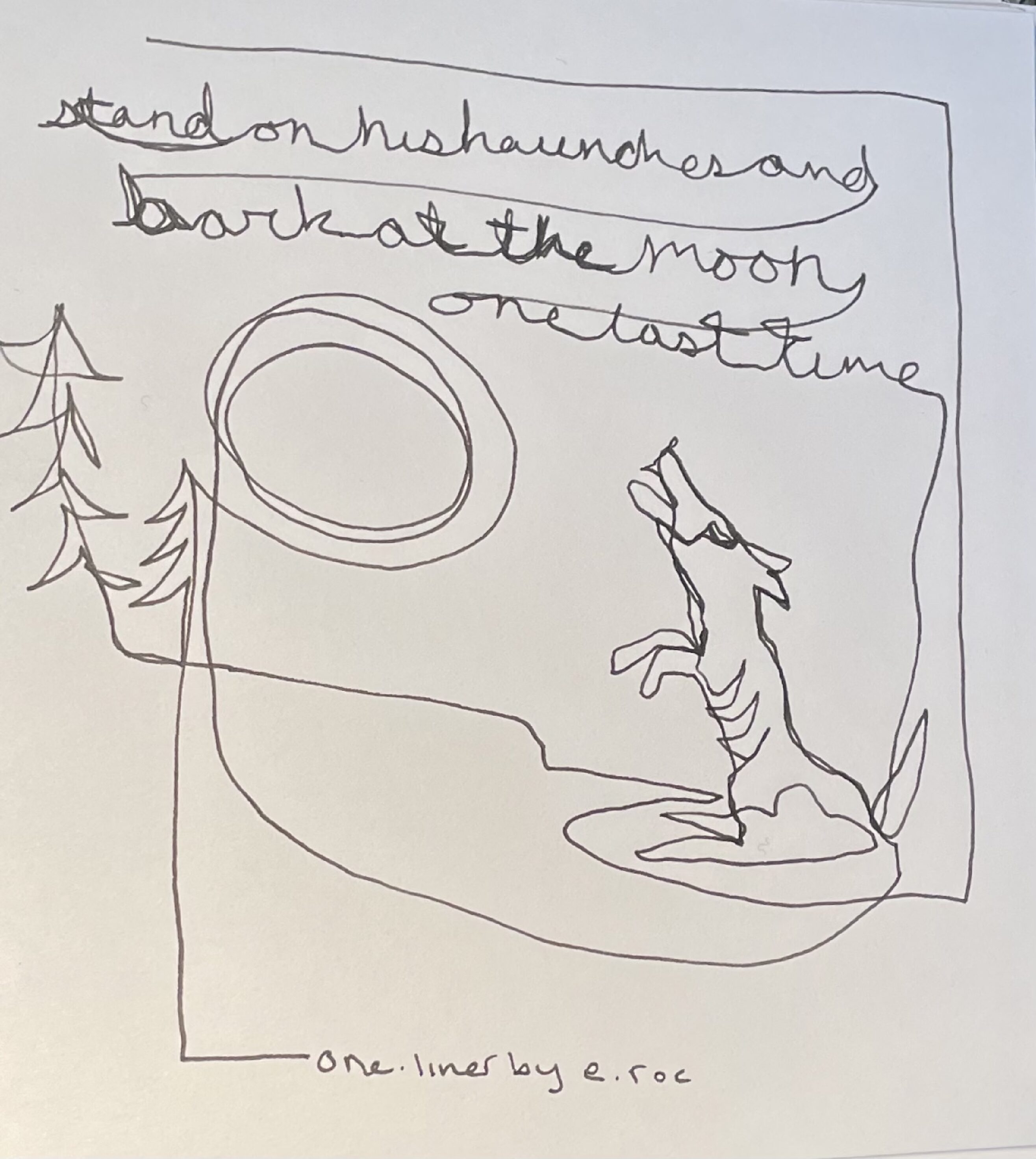

I had a dog once. He lived for 12 years. By the end, he smelled foul, soiled himself, and sprouted strange growths over his dry thin fur. Because he was a dog, his spirit never faltered, and I imagined that somehow he would just vanish, or dissipate, or stand on his haunches and bark at the moon one last time before dying instantaneously and happily, such that we could ignore the fact that he had just lost a battle with life.

This did not happen. The dog’s last months were agonizing, incremental, filthy, and decreasingly dignified. If I hadn’t loved that dog, I would have found him disgusting, because when the mystery of nonexistence begrimes us, we see it in our ignorance as foul and ugly and not beautiful. The dog, objectively, had become such a creature.

We finally put the poor dog down. A tall doctor arrived with hemlock for canines, and we lay around him and forced it down his throat. My father—who now faces a similar choice—lay with the dog as his head descended, his breath slowed, and his spirit departed. Soon, he lay dead and stiff, cooling palpably beneath our touch.

I don’t know where the dog went. In the confines of my own mind, I believe that he was here. And though I may stumble across facets of him in other dogs, in tree branches, in cloud formations, in dirt piles, and on the wind, I now know I will never find him again.

My father is dying. He will soon join that lowly dog in the infinity of non-existence, and it shall then fall to me to continue the parade in his absence. When my father dies, I know I will never find him again; just as I will never see that dog again. I may comfort myself with homilies about memories, and stories about lies, but the truth is, the rapture of nonbeing, as unknowable as a true circle, will have repossessed everything he is, was, and will ever be. He will exist then only in eternity.