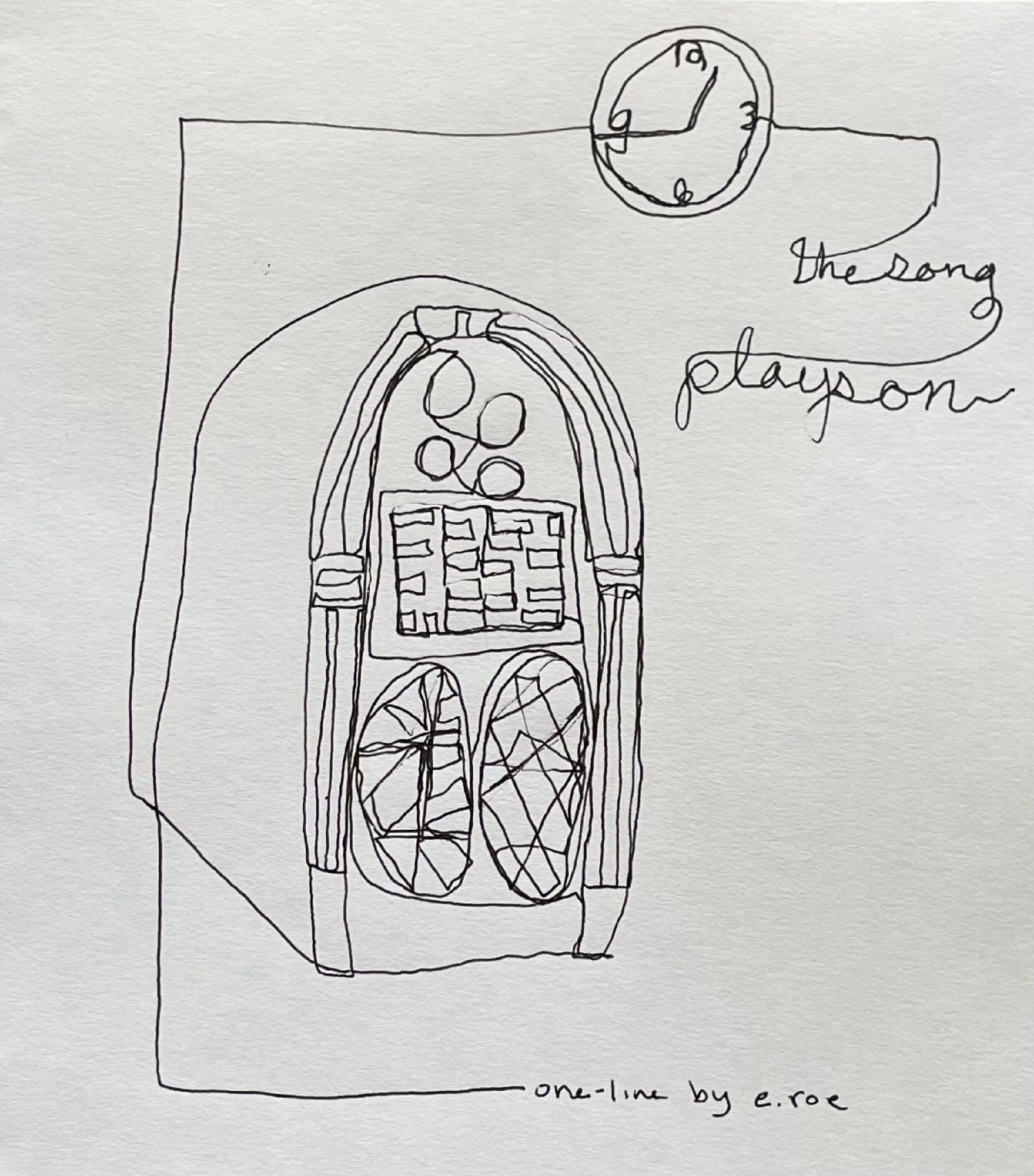

It begins the night before. After dinner—roasted beef, dark from the pot and a jacket potato your mother punctured and filled with butter—you went to your room and put in the tape from your prenatal yoga instructor. From the rug beside your bed, you breathed slowly and stretched, bending toward the parts of your body still within reach. It was cold outside, late December, but you were warm and calm. There was no snow; there would not be any until the new year. You went to sleep. When you woke it was the pit of night, nearly early morning. You felt the urge to piss, so you tumbled your belly out of bed and to the bathroom. You sat on the toilet but nothing came out. You went back to bed. You woke up an hour later with the same feeling—that stringent panic of piss, longing to be released. To the bathroom you went, but again produced nothing. It will take a third trip for you to start wondering. Not long after the third time, a deluge emerges, but it is not piss. You wonder whether your daughter will do this someday.

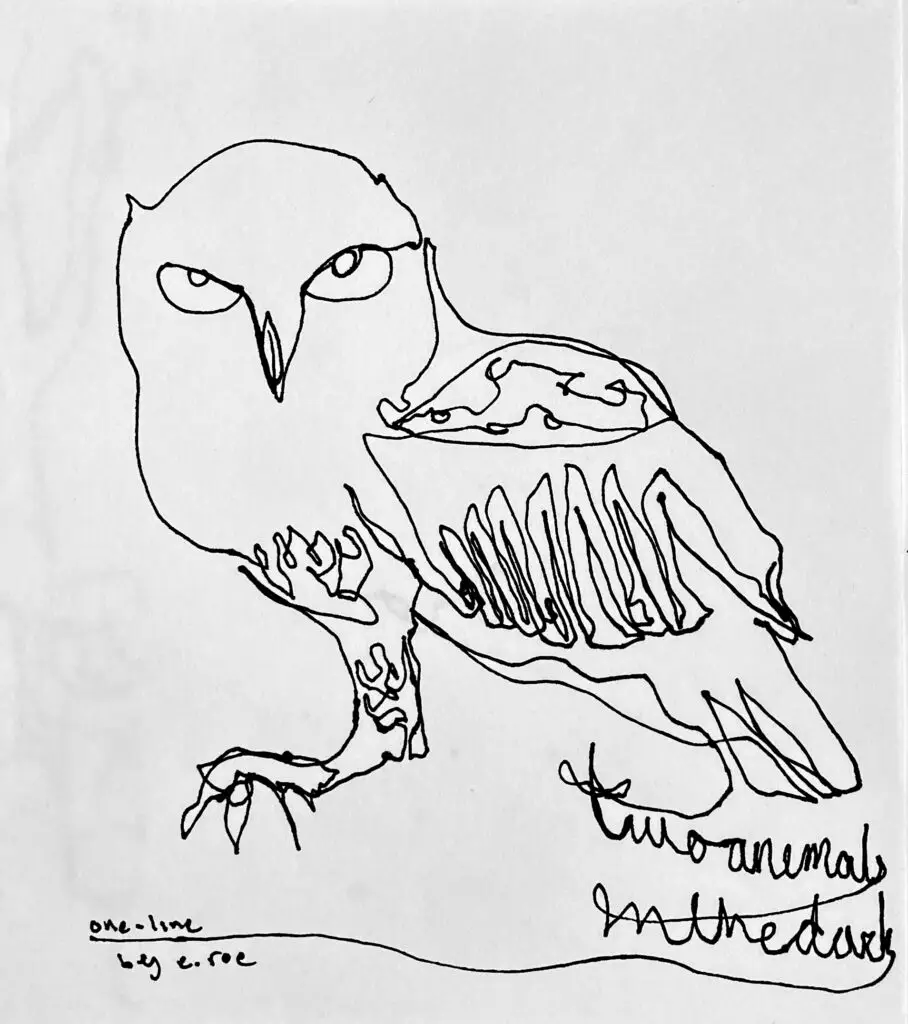

It begins a month before. You are walking in the not-quite forest next to your parents’ home. It is not quite a forest because there is a road that runs through it, cutting the collection of oak trees that have taken shelter here on these several acres of undeveloped land at the edge of a planned community on the fringe of the suburbs of this Midwestern capital. It is not beautiful, but it is the first winter you have seen outside of Texas for some years. There is no snow, but you can see your breath as you walk. You did not often get to see your breath in Texas, only in the early mornings and only part of the year; sweat is instead the way that your body registers its presence in the environment. It is almost fully night now, and you know you should head back to your parents’ place soon, but you like walking here, just another animal in the dark. The road before you branches into two separate strands, and you decide to turn around. At the junction, there is only one house; in a few years, this will all be lined with upper-middle-class families and fewer trees. You turn. Before you, in the tree that was at your back, there sits a snowy owl. You stop and stand there, looking at each other, two sets of eyes, yellow and brown. Two animals in the dark. Then he blinks, turns his head, and takes to the air. You stay there for a moment. You wonder what color your daughter’s eyes will be.

It begins in the spring, your favorite season in Texas. You meet a beautiful man, the friend of one of the kitchen guys. You split a bucket of beers after your shift. He has brown eyes, like yours. You spend a lot of time together, and it is good. It is so good. Then, after a while, it is less good. And then it is over. Well, not entirely. Not for you. You pack your things, leaving most of what you can for your roommate. You get on a plane and head North.

Now, North enough for naked oak trees and white owls and still no snow even though it’s almost Christmas, you walk the length of the house and call for your mother. She wakes; she comes. She asks questions and makes certain measurements of time and space. She has been through this before, more than nine times, actually. She wakes your father. She tells him to start warming up the car. Your back is hurting, but your mother tells you it will be okay. She has been through this before; it’s not yet time. Your mother leaves you on the couch while she goes to take a shower. You clutch at the hot water bottle that is supposed to be resting at the base of your spine, hefting it like you will your baby. Your father comes in from the garage, sweating, despite the December air. He asks you how you are. You, still holding the water bottle, tell him your back hurts. Without leaving the room, he turns in the direction of your mother, shower-bound, and shouts: “Her back hurts!” You wonder what kind of father you will be.